An Interdisciplinary Approach to Well-being and Recovery Post Natural Events in Puerto Rico*

Milagros A. Méndez Castillo, Roberto L. Frontera Benvenutti y Jaime Calderón Soto

University of Puerto Rico

Abstract

This article presents and discusses the model and strategies implemented by the University of Puerto Rico in alliance with the Hispanic Federation that addressed the psychosocial needs of people in Puerto Rico who had experienced a myriad of natural events. Short term outcomes included a total of 333 participants benefiting from 1,820 of direct therapeutic interventions and 4,145 people benefitting from indirect services. The interdisciplinary approach used for the delivery of services seemed to offer an encouraging and viable strategy/model to comprehensively understand and address the needs of affected people. Integrating specific disaster mental health training to the colleges and university curriculum, particularly for behavioral professional careers should be considered for future interventions. A university based interdisciplinary approach proved to be useful and should be replicated to deal with mental health services for people exposed to natural events.

Key words: natural events, hurricane Maria, earthquakes, emotional and social impact, Puerto Rican population.

Introduction

Puerto Rico as many other countries around the world are constantly exposed to natural events or hazards that can easily turn into a disaster if the underlying conditions for its occurrences go unattended. For the past five years Puerto Rico has experienced two hurricanes, continuous earthquakes, and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic. The need for the emotional care, because of these events, lead to the development, implementation and evaluation of PATRIA, a program designed to address the mental health needs of its population. Project PATRIA’s model for the delivery of direct and indirect services was interdisciplinary and accessible with an emphasis in recovery and preparedness. The purpose of this article is to present the model of intervention developed to address the needs of people and communities affected by such events/hazards.

Climate change and natural hazards

On defining climate, climate change, and adaptation to climate change (Shiva Salehi, Ali Ardalan, Abbas Ostadtaghzadeth et at, 2019) refer to the ability of system instability, sustainability, empowerment, productivity, flexibility, and transformation to climate change through the optimal use of resources, resistance, and coping, capacity building and opportunity creation. This definition is conceptual, it means that includes the main features of climateadaptation and is also functional that is, includes adaptation strategies for climate change. Much has been said about the effects of climate change and yet the public policies implemented have depended on the views about this issue. Since mid 1990s 2017 the United Nations and other world health organizations have (United Nations, 2022; World Health Organization, 2022)) have continuously stated that the change in climate is one of the biggest issues for all nations around the world to deal with. They noted that changes in climate change are the cause of agriculture losses, massive flooding, and lack of availability of running water, among others. The damage inflicted depends on the location, severity, and frequency. Mizutori (2020), from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, stated that one can reasonably argue that there is no such thing as a natural disaster despite the widespread use of the term in the media, by UN agencies, NGOs, and many others. Disasters, she argues, are the result of a natural or man/made hazards affecting a human settlement which is not appropriately resourced or organized to withstands impact, and whose population is vulnerable because of poverty, exclusion or socially disadvantaged in some way. A natural hazard becomes a disaster when it combines with exposure and vulnerability to carry loss of life, hurt and injury to people, along with economic loss. The Sendai’s framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 calls for the strengthening of disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk. The central point of this campaign is that “using natural” to describe a disaster can give people the impression that disasters are inevitable, and that human agency can do little to prevent or mitigate their impacts. In fact, on governance to manage disaster risk, Warren, Espaillat, and colleagues (may 22, 2019) reintroduced legislation to provide housing aid to victims of recent disasters of hurricanes Maria and Irma, Florence, flooding of the Missouri River basin and the wildfires in California.

Below, Wirtz & Guha-Sapir (2009) from the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disaster (CRED) and the Munich Reinsurance Company Munich (RE) have provided a disaster category classification and peril terminology for operational purposes [cred.b/node/564]. They have divided the natural disaster category into six disaster groups: Biological, (epidemic, insect infestation and animal stampede), Geophysical (earthquakes as of ground shaking and tsunami, volcano, mass movement—rockfall, avalanche, landslide, subsidence,) Meteorological (storm— tropical storm, cyclone), Hydrological (flood– flash flood, storm and mass movement –rockfall, landslide), Climatological (extreme temperatures, drought and wild fire) and Extra-Terrestrial (meteorite/asteroid) (Below and colleagues, 2009).

There are varying types of natural disasters that includes floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and many more. Estimates for the different types of natural disasters may range between 500-1,000 per year (pounditcafe.com/types-of-disasters-examples, oct. 22, 2017 science.world). Due to the climate change, we would expect this situation to increase instead of decrease. Thus, the need to explore models and framework for addressing the psycho-social effects of such disasters.

Mental health and natural hazards and disasters

The consequences of natural hazards converted into disasters can produce the death of loved ones, economic losses, and housing destruction, among others. Yet, the psychosocial consequences, although of most importance, are not as highlighted. Our experience (based on informal information from the VA PR Hospital, and two mental health clinics based in San Juan) was that following hurricane María most people who have visited the external mental health clinics had experienced a variety of symptoms that could be diagnosed as anxiety disorders, agoraphobias, panic attacks and depression. The Puerto Rican Government reported that the overall suicide rate rose by 29 percent in 2017 (NPR, May 2018), while suicide-related calls to the government run hotline doubled from August 2017 to January 2018 (USA Today, March 2018). However, the aftermath of natural hazards (i.e., loss of employment and income, property damages, marital stress, health conditions, home displacement, among others) can bring the best out of people. We were able to witness a great sense of community cohesiveness, personal societal empathy, and true desires to help others in need. The same aftermath experiences can bring opposite behaviors. We were able to witness and has been well documented in the mayor Puerto Rican newspaper the greed, and acts of corruptions at the individual and governmental levels (i.e., one senator was accused of withholding goods, that were later expired, for distribution only in her constituents’ district and only if the press was present). In fact, DeWolf (2000)–from the training manual for mental health and human service workers in major disasters– have described six phases of recovery related to how an individual or community may feel the effects of a disaster: 1) Pre-disaster, 2) Impact, 3) Heroic, 4) Honeymoon, 5) Disillusionment, and 6) Reconstruction.

The experiences of a natural hazard will, in many cases, bring out signs of emotional distress (sadness, loss, hopelessness, disorientation, isolation, disorganized thoughts) which, although unpleasant, do not necessarily signify a mental health disorder; and are in fact, expected during these tired circumstances. Some of these signs can worsened overtime but can be manageable.

Those same experiences can worsen the vulnerability to mental health issues post disasters (Goldman y Galea, 2014), affecting the quality of life which can induced more pathological manifestations, leading to the development of mental health disorders such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD), depression and anxiety disorders in children, adolescents and adults (Brown et. al, 2017; Derivois et. al, 2014; Krug et. al., 1998; Pfefferbaum et. al, 2016; Rivera y Arroyo, 2017; Tang et. al, 2014; Weems et. al, 2016).

Natural hazards and Puerto Rico

Over the last five years (since September 2017 till present) Puerto Rico has experienced, different types of hazards. We have been impacted by a biological natural hazard in the form of the Covid-19 pandemic (since January 2020, just as the rest of the world), geophysical hazard in the form of the constant and present earthquakes experience (also since January of 2020) in the south part of the island, meteorological hazard in the form of tropical storms and the hurricanes Irma and Maria that affected the island in September 2017, and Hydrological hazard caused by the tropical storms that often are experienced in the island in the form of flash floods.

Unprecedented damage from hurricanes Irma and María devastated the US territory of Puerto Rico. The entire population of the island was left without electricity for months. Municipalities located in the southeast and center of the country that were in the hurricane path are to this day very vulnerable. Today, five years later after hurricanes Irma and María, there are still about 3,646 houses covered by the FEMA blue tents (Cynthia López Cabán, jayfonseca.com, May 25, 2022; y www.noticecel.com may26,2022 3:31Leoncio Pineda Dattari) and many other that need significant reparations while the current hurricane season is about to begin, once again.

Five years after hurricanes Irma and Maria, relief funds are yet to come for the hardest hit Puerto Ricans. For this current year (2022) the Puerto Rican government has barely initiated the process of call for proposals to initiate the reconstruction of housing. While the Department of Housing from the US R3 program (R3) covers repairs for minor damage in flood and landslide zones, it does not offer reconstruction of homes for substantial damaged properties. By 2018, It was estimated that approximately 400,000 to 500,000 American citizens residing in Puerto Rico have emigrated from the island due to the hurricanes, mainly to United States, particularly to the State of Florida (El Nuevo Día, April 2018).

In the Caribbean we are in constant threat of being hit by a hurricane, and Puerto Rico is no exception as it is in the clear route for hurricanes; the possibilities of been hit by another hurricane in the near future are very high. For the 2022 alone, the weather forecasters (The Hill, 2022) has already predicted an above normal season. Specifically, the forecaster predicted 16-20 named storms. Of those, three to five of the storms are predicted to reach hurricane status for Puerto Rico and the Caribbean region, as the current hurricane season begins June 1 and lasts until November 30 of every year. Yet the country, its Department of Health and mental health sector, were not properly equipped for the 2017’s hurricanes and the 2020’s earthquakes, and continue to be unequipped to meet the mental health needs of the population. People were emotionally and physically unprepared for these events and the island’s limited number of professionals specifically trained to deal with natural hazards and mental health stressors lacked capacity and coordination, thus the urgent need to develop strategies that can better address the psychosocial needs of people affected by such events.

A university based Interdisciplinary-multilevel approach to direct and indirect services

To address the mental health needs of the Puerto Rican population the directors from three Departments of the College of Social Sciences of the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) developed Project PATRIA to provide interdisciplinary mental health services to the people of Puerto Rico affected by Hurricane Maria or may be affected, in the future, by another natural disaster.

Project PATRIA (Spanish acronym for Project targeting Empowerment, Transformation and Recovery through an Interdisciplinary approach of Accessible Services) was developed through a collaborative agreement with The Hispanic Federation foundation for financial support. The Hispanic Federation is a private non-profit organization founded in 1990 whose aim is to empower and advance the Hispanic community, support Hispanic families, and strengthen Latino institutions through work in the areas of education, health, immigration, civic engagement, economic empowerment and the environment. It has strong presence in New York, Florida, North Carolina, and Puerto Rico (Hispanic Federation, 2022).

The interdisciplinary approach. This project was designed and implemented by professionals and graduate students from the fields of social work, rehabilitation counseling, and psychology. Students from those three disciplines have found in PATRIA a practicum/internship site like no other in Puerto Rico for enhancing their academic/professional development in a program specialized in disaster’s mental health.

Although each discipline has its own definition, roles, and functions, for this project the roles and functions of each were asserted, but also, in many ways redefined. During most of the project activities, a professional or graduate student from each of the disciplines was equally involved. For instance, once a prospective participant was admitted to services a co-therapeutic team of graduate students from the three mentioned disciplines, supervised by a licensed professional, proceeded with the intervention. This project also aimed to impact the ongoing, now evident, shortage of mental health professionals with formal training in rapid psychosocial support and intervention (first aid and treatment) for people affected by natural events/disasters. PATRIA formally trained a cadre of professionals from psychology, rehabilitation counseling and social work in disaster’s mental health and preparedness. This interdisciplinary approach lied the foundation for the project, that is, the accessibility and multilevel approach, the direct and indirect types of services all were conceptualized and offered from such framework. All of services were conceptualized and offered by the interdisciplinary team described above. Accessible Services and its multilevel approach. PATRIA offered its direct and indirect mental health services via three different types of settings. The settings included three UPR’s campus clinics, nine Community Based Organizations (CBO), and the participant’s home if needed. By bringing services to 12 geographically diverse sites, the project also addressed the dearth of services in regions beyond the metropolitan area of San Juan.

Recovery and Preparedness. PATRIA developed mental health services with specific objectives, being the most important ones Recovery and Preparedness. The concept of preparedness is central for Project PATRIA, as we ascertain that people need to feel empowered to be able to transform many aspects of their daily living in order to be prepared for future natural events like hurricanes and earthquakes. The concept of preparedness is preceded by the concept of recovery from their previous emotionally challenging (and for many traumatic) experiences resulting from a catastrophic natural hazard. Another strategy to address these two concepts, preparedness and recovery, was the development of PATRIA’s Certificate for Continuing Education that targeted the country’s capacity to better prepare and respond to natural events/disaster. This certificate is designed for all employees in the public and private sector that are somehow involved in servicing people and communities affected by these events.

The complex and diverse needs of citizens who were severely affected requires a comprehensive service delivery approach best served by an interdisciplinary team of professionals.

Description of services

The road to recovery requires a diversity of direct and indirect services.

This project had two objectives: (1) To offer direct services and (2) to offer indirect services (preventive services and professional development services) to those indirectly affected by hurricane Maria.

Direct Services. This Project provided mental health services for the treatment of varying symptoms related (though not exclusively) to the aftermath of disasters (i.e., major anxiety, major depression, PTSD, conduct disorder, suicidal ideation, etc.). These services were very much accessible to people in need as they were provided either at each university site, the

CBO’s, or at the participants’ homes. Students providing direct services were those at the Professional Internship Level of their graduate education (doctoral or masters) for the three specialty areas and second year students enrolled in clinical practicums. The supervising Clinical Psychologist stationed at the three university centers also provided direct services. These services included the evaluation, treatment, and management of individual needs of people dealing with the aftermath of María (i.e., which includes acute stress disorder, acute stress reaction and PTSD). A brief description of direct services follows:

- Evaluations. Include diagnostic and psychological evaluations; assessment and diagnosis of functional capacity; rehabilitation potential for daily living activities, social integration, work and employment; Development of an Individual Treatment and/or Rehabilitation Plan (Interdisciplinary Team). Among other tools, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was used as a diagnostic tool.

- Counseling. Individual and group counseling for fostering psychosocial adjustment to illness, self-reliance, empowerment and effective interdependent living skills.

- Psychotherapy. Individual, group, couples, and family psychotherapy for treatment of daily and chronic mental health situations targeting trauma (i.e., PTSD, suicidal ideation, marital dysfunction).

- PATRIA Trabaja. PATRIA Trabaja was an occupational exploration initiative for people that have lost their jobs as the result of natural events. It consisted of occupational counseling, assessment and exploration of interests, aptitudes and work values.

All of these direct services were aimed at helping people identify their strengths and weaknesses, to help them recover from the emotional strains of past experiences, and to help them to be better prepared for coping with future events.

Indirect services (preventive services)

- Disaster Preparedness. The project personnel had planned to conduct a comprehensive interview or Voluntary Census (VC) of people with mental health and physical (chronic illnesses and disabilities) needs to assess and monitor participant’s needs and disaster preparedness. This project objective was not fully accomplished due to several limitations mostly related to the COVID 19 measures implemented by the government health authorities. VC participants were to be identified throughout several communities in the island in terms of their resources and vulnerabilities when facing natural events and disasters. After the structured and comprehensive interview is conducted, a PIPEN was to be developed jointly by PATRIA’s personnel and family members. A PIPEN is a written individualized preparedness plan for natural events and disasters. As proposed, the main purposes of the VC/PIPEN were:

- 1. to assist participants with being better prepared for future natural events/disasters;

- 2. to assist participants develop, assess and strengthen their support systems; and

- 3. to assist community, public and private organization in their capacity to monitor participants before and after the next catastrophic event, which includes developing and testing rapid and effective responses. With participants’ permission, the VC/PIPEN was to be shared with community organizations, municipal authorities and private health services providers; the VC was to include: name of patient and caretakers (family members, legal guardian), address and contact information (telephone numbers, email, relatives living elsewhere), transportation needs, communication needs and treatment needs (medications, assistive technology, medical equipment, etc.) among others.

- Strengthening Support Systems (SS). The project conducted individual and group psycho- educational interventions for the development of an effective support system (SS); including family, community and professional components to the SS; and skills for evaluating the adequacy of their SS and network.

- Strengthening of CBO. The project promoted capacity building of CBO’s through continuing education, development of program evaluation skills, consultation, development of work plans to prioritize their needs, promotion of self-mobilization to increase the community’s socio-economic development, sustainability of projects, and development of better practices in human resources including psycho-educational workshops for human resources, especially as it relates to increasing employee burn-out and wellness post-disaster.

- Adherence to Treatment. Individual and group psychoeducational interventions central to mental and physical health recovery were offered to foster Adherence to Treatment (ATX) including psychological, psychiatric and medical services; Group psycho-educational interventions (group) were offered to promote self-awareness and knowledge of illness and ATX needs; and individual follow up sessions were scheduled targeting ATX.

- Promotion of well-being. The project conducted group psychoeducational activities that integrated art/dance therapeutic strategies directed to improve quality of life and develop skills and for planning and coping with stressful life events; and group psycho-educational interventions (group) directed to enhance wellness and a healthier life style were regularly available and offered.

Implementation Procedures

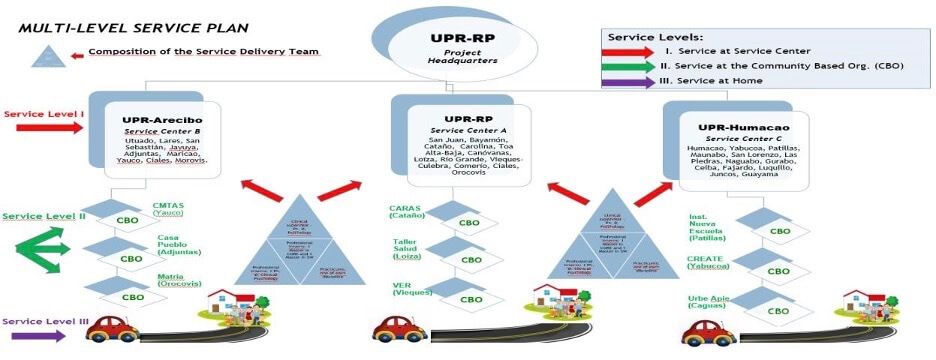

The services were provided using three layers of services (See diagram). These levels of services helped us ensure that all of the services provided were truly accessible to the people and communities in need for services. The first level of services was at the University Campus, the second at the Community Based Organization (CBO), and the third at the homes of most in need. Three regions of the country were selected. The University of Puerto Rico (UPR) is composed of 11 Campuses each representing a geographical region of the island (about 1-2 hours apart). The selection of the sites, namely the University’s Campuses and the CBOs, was done in partnership with the Hispanic Federation and in agreement with the selected sites. The University of Puerto Rico is organized into 11 different campuses distributed to service the entire island. We had initially proposed to service three regions of Puerto Rico through the involvement of four of our Campuses, namely, the Río Piedras Campus (to address the needs of the metropolitan area of San Juan), Arecibo (to address the needs in the north central part of the island), the Humacao (located in the south east part of island and where hurricane Maria did significant damage), and Ponce (in the south part of island where the earthquakes has hitting the most). Once the final selection was made formal agreement was developed with each campus.

Community Based Organizations: The nine CBO sites were selected in collaboration with the HF. One of the criteria was that they were located in the geographical region of one of the chosen Campuses. At these sites, interdisciplinary teams of graduate students were placed to offer the services under the supervision of the regional psychologists and the CBO’s psychologist (if available). CBO’s each received some small funding for their collaboration.

Home Visits: Individuals in need of services but unable to attend the University clinics or the CBO site, were serviced through weekly or biweekly home visits. The following is a picture with the model of intervention (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Model Intervention

Service Provision Framework

The service provision framework consisted of about 25 to 30 Graduate Students per semester under supervision of four Licensed Clinical Psychologists. One of the Clinical Psychologist also served as Project Coordinator. The project was closely supervised and monitored by the PI, Co-PI. from the three disciplines.

Students: For years one and two about 60 students were involved in the project, as they receive a stipend for their time in the project. At the internship level, a total of 15 students per year were involved (6 MA/SW, 6MA/CORE, 3PhD in Clinical Psychology). Clinical Psychology Interns were 4th year doctoral students who had taken all of the coursework and practicums; they were to complete 2,000 hours a year internship with the project. MA level students from the Social Work and Rehabilitation Counseling programs performed a 600 hours internship per semester. At the Practicum level, a total of 36 graduate students per year were involved in this project (6 MA/SW, 6MA/CORE, 24MA/PhD). For the delivery of direct services, only second year students enrolled in Clinical practicums (practicums III, IV and V for a total of 10 hours a week (total of 450 hours a semester) were allowed to provide services under the supervision of a licensed psychologist.

Faculty at the UPR. Full-time faculty from the graduate programs at UPR were involved in the development, implementation and evaluation of the project. Full-time and part-time faculty were involved in the supervision of the graduate students at the intervention sites. In the psychology program a student can register in practicum III, IV and V for direct services, and in any other 3 practicums in each of the specializations (social community, academic, and IndustryOrganization). It means that for the Psychology Department, 6 professors/supervisors may be supervising practicum students. For the Social Work and Rehabilitation Counseling programs a student can register in one practicum course with a UPR professor in charge of supervision. For the internship students, the psychology program provided one supervisor for the three interns. Each SW and CORE internship student was supervised by one UPR professor. Thus, a minimum of 15 UPR professors/supervisors provided supervision to students at no cost for the project (6 psychology practicums supervisors + 1 psychology internship supervisor + 2 SW and CORE practicum supervisors + 3 SW internship supervisors + 3 CORE internship supervisors).

Supervisors at the intervention sites. A total of three full-time licensed professionals from the fields of social work, rehabilitation counseling and psychology were contracted to provide onsite supervision of students and also provided direct clinical services at each intervention site of the pilot program.

Short term outcomes for direct and indirect services

For the first year of the project, preliminary data shows that direct and indirect services were able to be provided. In terms of direct services, three hundred thirty-three (333) participants had received 1,820 interdisciplinary therapeutic interventions, totalizing 2,237 session hours and representing 3,230 of PATRIAS’s resource/hours effort. Participants have benefited an average of 5 interdisciplinary sessions each. The most common therapeutic goals worked during therapeutic interventions are coping skills, vulnerability, support systems and specific mental health symptoms. Overall, participants continued to be mostly female (66%); 68% of the participants were 24 years old or less, 9% were 61 years old or more. For indirect services PATRIA offered 373 hours of indirect services to 4,145 people. Services offered took place mostly at the community level (3,251/4,145 = 78%), followed by people served at the CBO (448/4,145 = 11%) level. PATRIA’s indirect services have spread to near 72 community settings across the island. Hours invested in indirect services continued to be offered mostly at the community level (69%) followed by the CBOs (21%). The most common workshops offered (based on number of people impacted) are Say no to bullying, Stress and anxiety management, Getting to know my emotions through art, Mental Health First Aid, and Vicar trauma fatigue due to compassion and self-care.

Challenges

PATRIA’s intervention team experienced community stigma related to looking for and receiving mental health services. Stigmatization of people in need of mental and emotional health services must to be addressed from a community health approach. It is important to convey that even though people may have undergone a traumatic experience, that does not imply that they are clinically traumatized by that event; nor that that they are significantly dysfunctional. To fear or to feel hopeless are all natural emotions; those emotions do not equate to a mental illness, and mental illness itself is not different from other accepted physical health conditions.

Lessons learned

The Caribbean region is vulnerable to Natural hazards/events such as hurricanes and earthquakes. We must begin to conceptualize these events as natural events/hazards and NOT necessarily as DISASTERS. The focus on preparedness should not be IF but WHEN (hurricanes come yearly, more often and stronger!). Understanding hurricanes (and earthquakes) as Natural Events is important for mental health delivery. Preparedness will help us reduce the probability of a natural event becoming natural disaster. Being prepared at the individual, family, community and government level will reduce the probability of a natural event becoming a disaster. Preparedness can help us move from hopelessness to self-reliance, preparedness and prevention, which means saving lives!

Our focus should be on the development of strategies that empower people, through an interdisciplinary approach, to overcome feeling of inadequacies, dependencies, helplessness and hopelessness. General wellness and quality of life as therapeutic goals, will reduce the stigma for receiving psychological services.

Mental health services should include a plan for recovery, which includes the development of coping skills at the emotional and practical level, self-reliance, healthier lifestyles, relapse management and prevention, psychosocial adjustment, skills for obtaining and retaining a job, and skills for interdependent living among other therapeutic goals (rather than independent living).

These therapeutic goals can only be achieved by a well-articulated interdisciplinary team that has been formally trained to work from such perspective, with a supervisory team that is also interdisciplinary, and the development of a comprehensive needs assessment.

Mental health services and programs should be truly accessible to all people including people with diverse functional capacities. Accessible mental health services include, among many other aspects, the following: an open admission policy to services (no need for referrals), free of charge services, services that are in physical proximity to people in need and their communities, and home visits as part of the menu of services. Home visits are costly and time consuming, but they will make services accessible to the most vulnerable people, that is, the elderly and people with significant physical and psychiatric disabilities.

For mental health community programs to be successful there must be partnerships with CBOs. CBOs know the history of the community, understand the community needs, have already identified individual needs and have access to communities. CBOs should evolve into mental health services providers; that will certainly challenge the stigma related to mental illness and will make services readily accessible.

There is a need for health professionals (particularly mental health providers) that are specifically trained in trauma management and recovery from natural disasters (Disaster Mental Health). In PATRIA, our supervisors and graduate students received over 100 hours of training in Disaster Mental Health in a year. We are now proposing a 60 hours Professional Certificate in Disaster Mental Health to be offered by the UPR´s Continuing Education Office

The interdisciplinary approach proved to be effective to better understand and address the needs of affected people. Integrating specific disaster mental health training to the colleges and university curriculum, particularly for behavioral professional careers should be considered. This model can provide a country with a cadre of professionals for current and future events.

References

Below, R., Wirtz, A. y Guha-Sapir, D. (2009). Disaster Category Classification and peril Terminology for Operational Purposes. https://www.cred.be/node/564

Brown, A. (2019). Weathering the storm. The intercept. https://www.the intercept.com/2019/09/22 puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-disaster-relief/

Brown, R. C., Witt, A., Fegert, J. M., Keller, F., Rassenhofer, M., & Plener, P. L. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents after man-made and natural disasters: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological medicine, 47(11), 1893-1905. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000496

Derivois, D., Mérisier, G. G., Cenat, J. M., & Castelot, V. (2014). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and social support among children and adolescents after the 2010 Haitian earthquake. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19(3), 202-212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2013.789759

DeWolf, D. (2000). Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters. DHHS Publication No. ADM 90-538. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Editorial El Nuevo Día (8 de septiembre de 2019). We must work on a culture of prevention. El Nuevo Día. https://www.elnuevodia.com/english/english/nota/wemustworkonacultureof prevention-2516564/.

Hispanic Federation (2022). Mission and History. https://www.hispanicfederation.org/about/mission_and_history/

Kishore, N., Marqués, D., Mahmud, A., Kiang, M. V., Rodriguez, I., Fuller, A., Ebner, P., Sorensen, C., Racy, F., Lemery, J., Maas, L., Leaning, J., Irizarry, R. A., Balsar, S., & Buckee, C. O. (2018). Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. The New England Journal of Medicine, 379, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1803972.

Leblanc, J. (2018). Disaster Psychosocial Services: a unique provincial approach to psychosocial response in British Colombia, International Congress of Applied Psychology (ICAP), Montreal, Canada.

Mitzouri, M. (July 16, 2020). United nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Preventionweb.net/experts/oped/view/72768.

Pfefferbaum, B., Jacobs, A. K., Van Horn, R. L., & Houston, J. B. (2016). Effects of displacement in children exposed to disasters. Current psychiatry reports, 18(8), 71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0714-1

Rivera F., A. & Arroyo Q., C. (2017, diciembre) Impacto del Huracán María en la Niñez de Puerto Rico: Análisis y Recomendaciones. Instituto del Desarrollo de la Juventud. http://juventudpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/19473.pdf

Tang, B., Liu, X., Liu, Y., Xue, C. & Zhang, L. (2014). A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health 14(623), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-623.

Science World (2017). (pounditcafe.com/types-of-disasters-examples) oct. 22, 2017

The Hill (April 13, 2022). https://thehill.comnews32663.

United Nation (2022). Un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change.

Warren, E & Espaillat, A. (2019). Legislation to provide stable housing. www.warren.sanate.gov/.newaroom/.press-realeases/warren-espaillat-collegeaguesreintroduce=legislation-to-provide-stable-housing-for-survivors-of-natural-disasters]

Weems, C. F., Russell, J. D., Neill, E. L., Berman, S. L., & Scott, B. G. (2016). Existential anxiety among adolescents exposed to disaster: linkages among level of exposure, ptsd, and depression symptoms. Journal of traumatic stress, 29(5), 466-473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22128.

Shiva Salehi, Ali Aedala, Abbas Ostadtaghizadeth, Gholamreza Garmaroudi, Armin Zareiyan & Abbas Rahimiforoushani (2019). Conceptual definition and framework of climate change and dust storm adaptation: a qualitative study. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, Vol 17, 797-810.

World Health Organizations (2022) Euro.who.int/-data/assets/pdf-file/009/397791/SD6-13policy-brief.pdf.

* This project was financed through a collaborative agreement with the Hispanic Federation. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Milagros Méndez, University of Puerto Rico, PO Box 23174 San Juan Puerto Rico, 00931-3174

e-mail: milagros.mendez@upr.edu